All throughout the last two pandemic years, Anna Elise Johnson went on quests, some which took only one day, others a little longer. They were relatively modest, manageable quests––still demanding in that they involved driving, hiking, scouting, hours of solitude, but they never required exorbitant resources––to find different geologies (red rocks, desert vistas), and make work in and with the earth. She typically went alone out into barely inhabited places. When I saw her, she would mention where she had been most recently: which county, which adjacent state. I started to expect this, like you expect other people to talk about their work.

But this kind of questing has its own particular history. Because the gallerist and patron Virginia Dwan passed last week, I have been thinking more than usual about this. Dwan, who would go on to fund Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty and Michael Heizer’s Double Negative, started going on scouting missions with Smithson early on––and because she herself had no ambitions to make her own earthworks, to quest itself felt like the point. This desire to be out in the vastness remains relatable, even as given our current self-awareness of manmade damage, the days of making huge gashes or forms perhaps best seen from private planes feel passé. “It is difficult to imagine ourselves existing in the same cultural realm as artists of the past,” Johnson wrote for Psycho Geology, the group show she curated in February. She wondered, also, if art could “paradoxically phenomenalize our lack of agency as a geological force.” The show proposed that there was something afoot, in how Johnson and other artists were grappling with the landscape as we came to understand the urgency of climate change (a phenomenon that is both caused by human action and makes individual humans feel especially small). I recalled this yesterday when, in a theory class I teach, a student wondered if the Anthropocene is itself a new art movement.

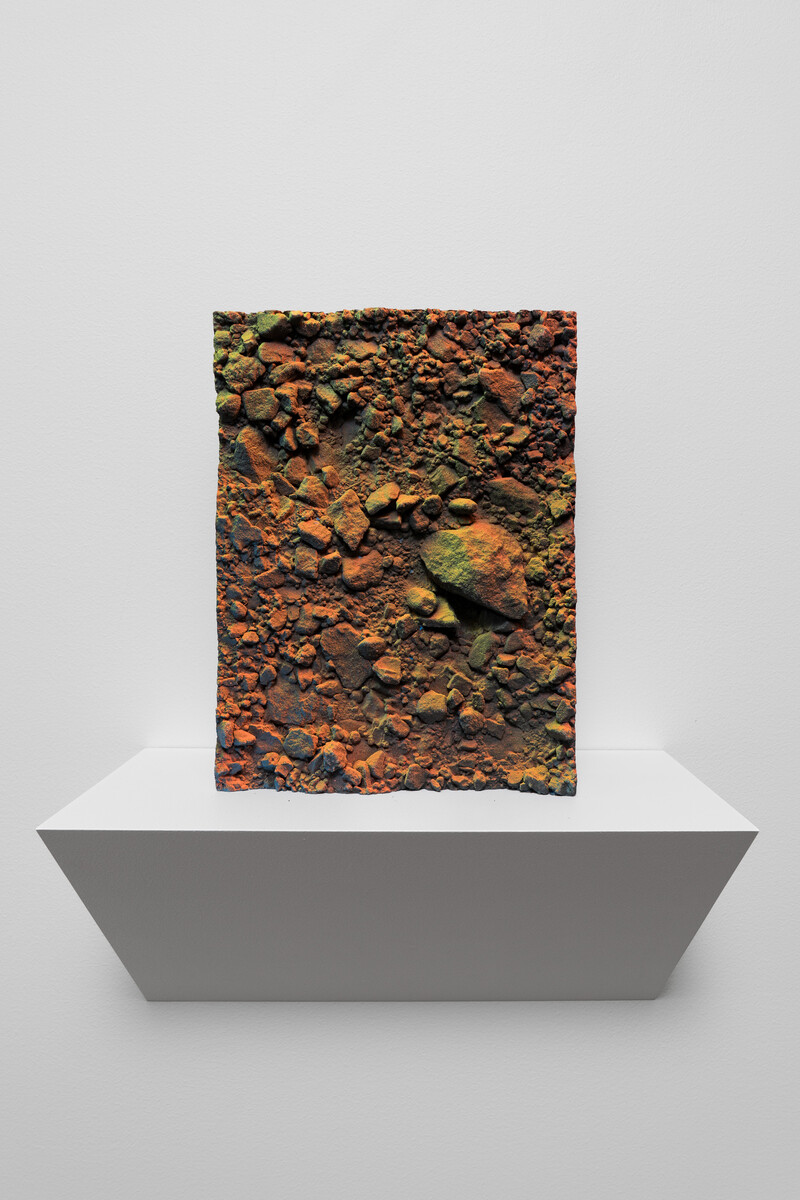

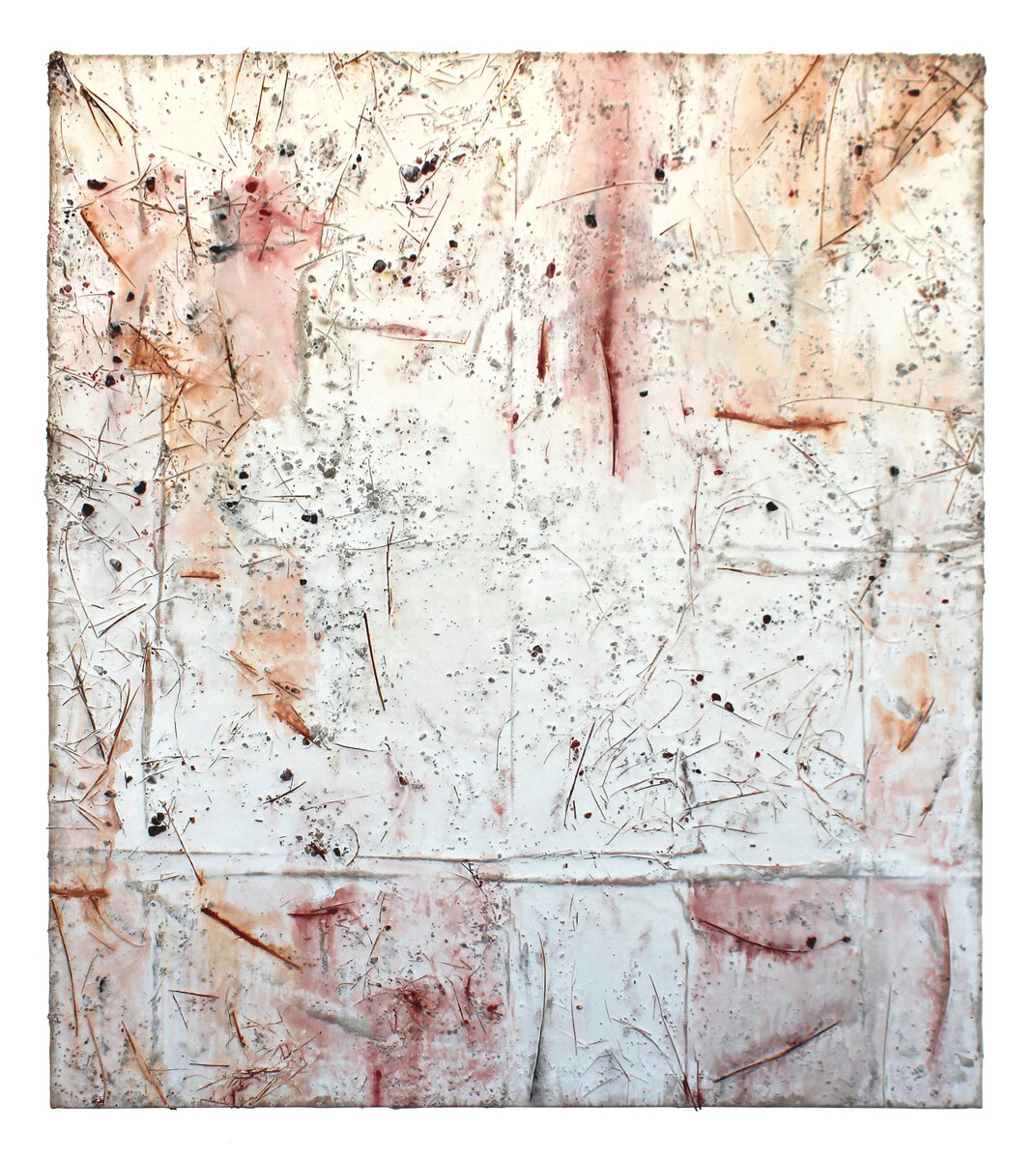

When the Nouveaux Réalistes all gathered in Yves Klein’s Paris apartment to form their own movement in 1960, they declared themselves against the art establishment’s intransigence, its refusal to acknowledge the urgency of reality—why for instance were so many ignoring the Algerian War? Whereas the Réalistes meant to embrace “the whole of sociological reality,” to acknowledge it without “any aggression complex, without typical polemic desire.” Their works funnily enough tended still to be paintings––paintings that incorporated found objects, sand, dirt, fire. For them, the problem was the way certain painters painted (i.e., Abstract Expressionists), never the medium. Johnson’s Earthwork are typically paintings (her sculptures are also rectangular like paintings, though much denser). She begins each the same way: in the landscape, adding earth and material (plaster, gesso, water color) to a canvas until it records the typography of the ground. Early on, the Earthworks remained abstract, then they began playing more with “reality” and what that means and looks like in painting.

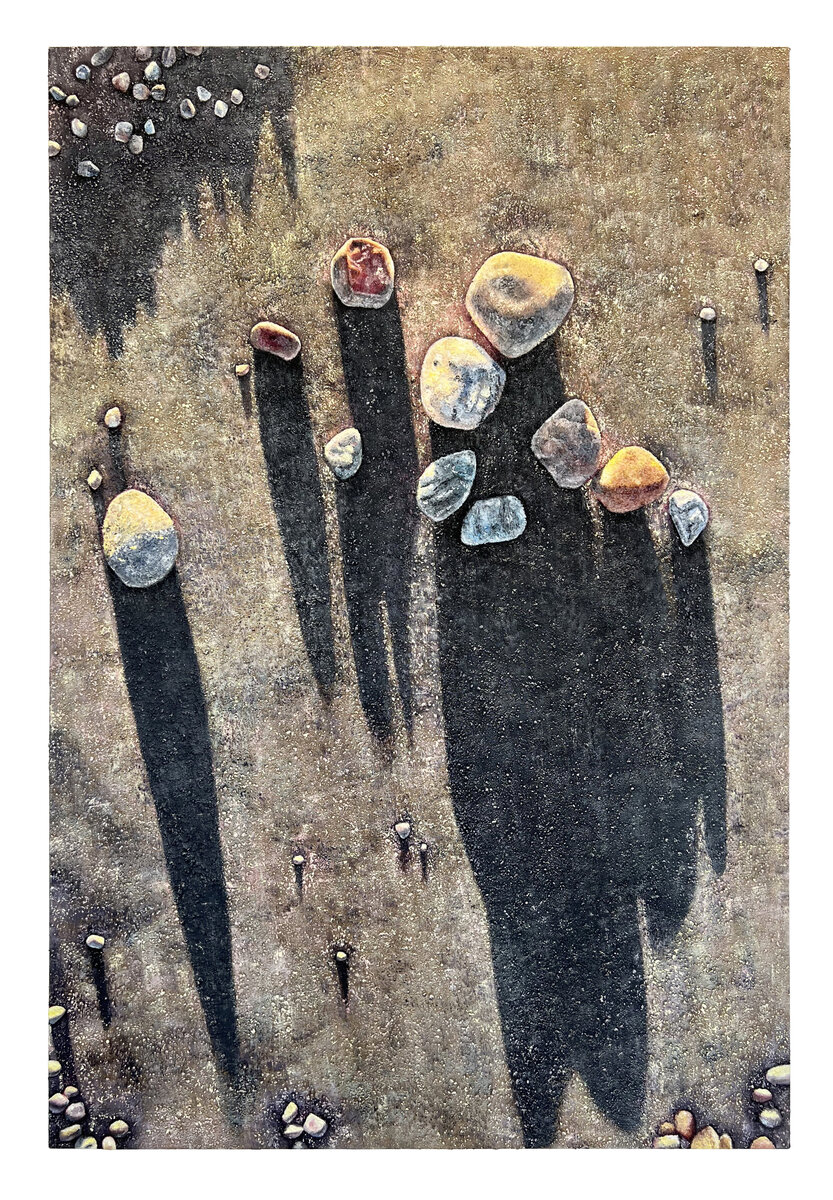

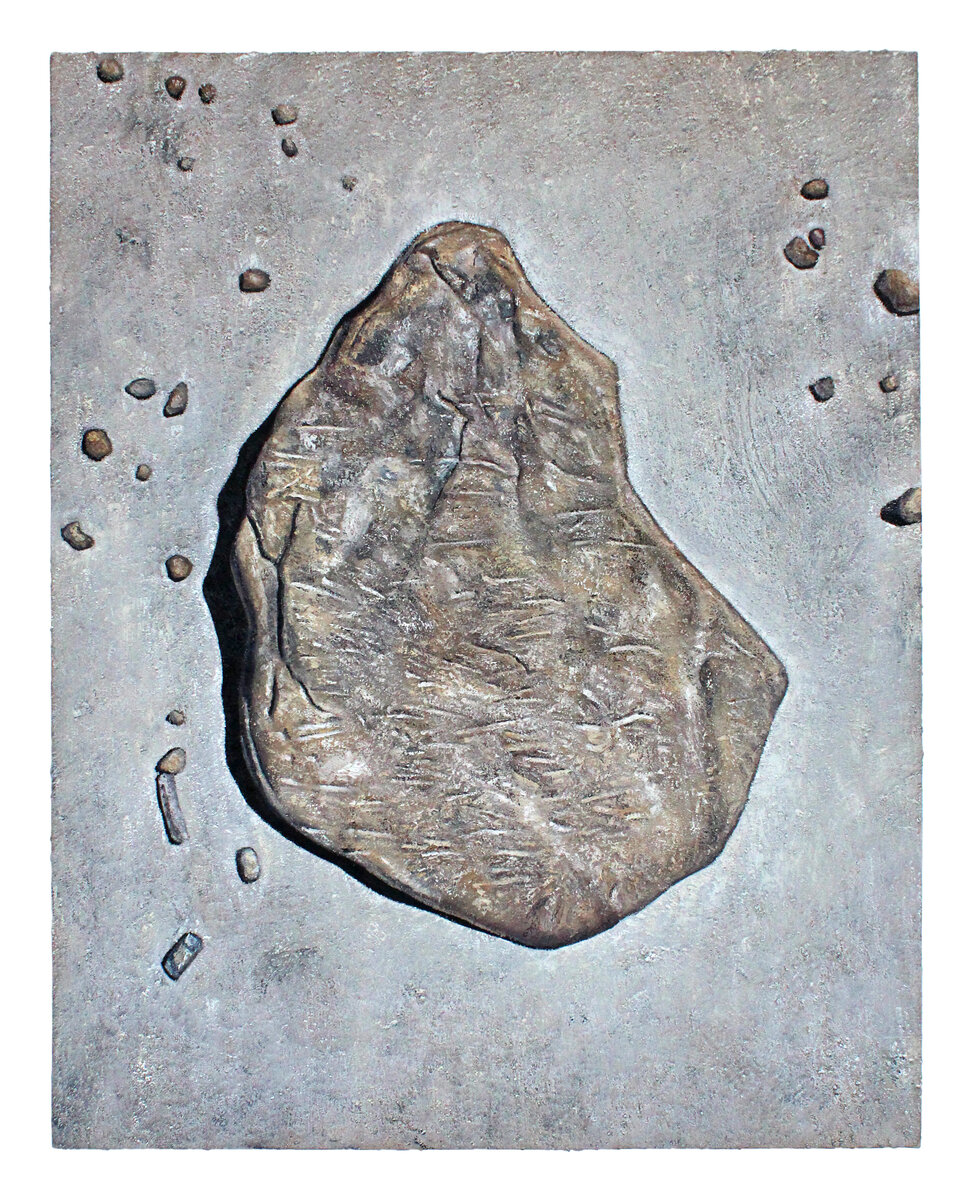

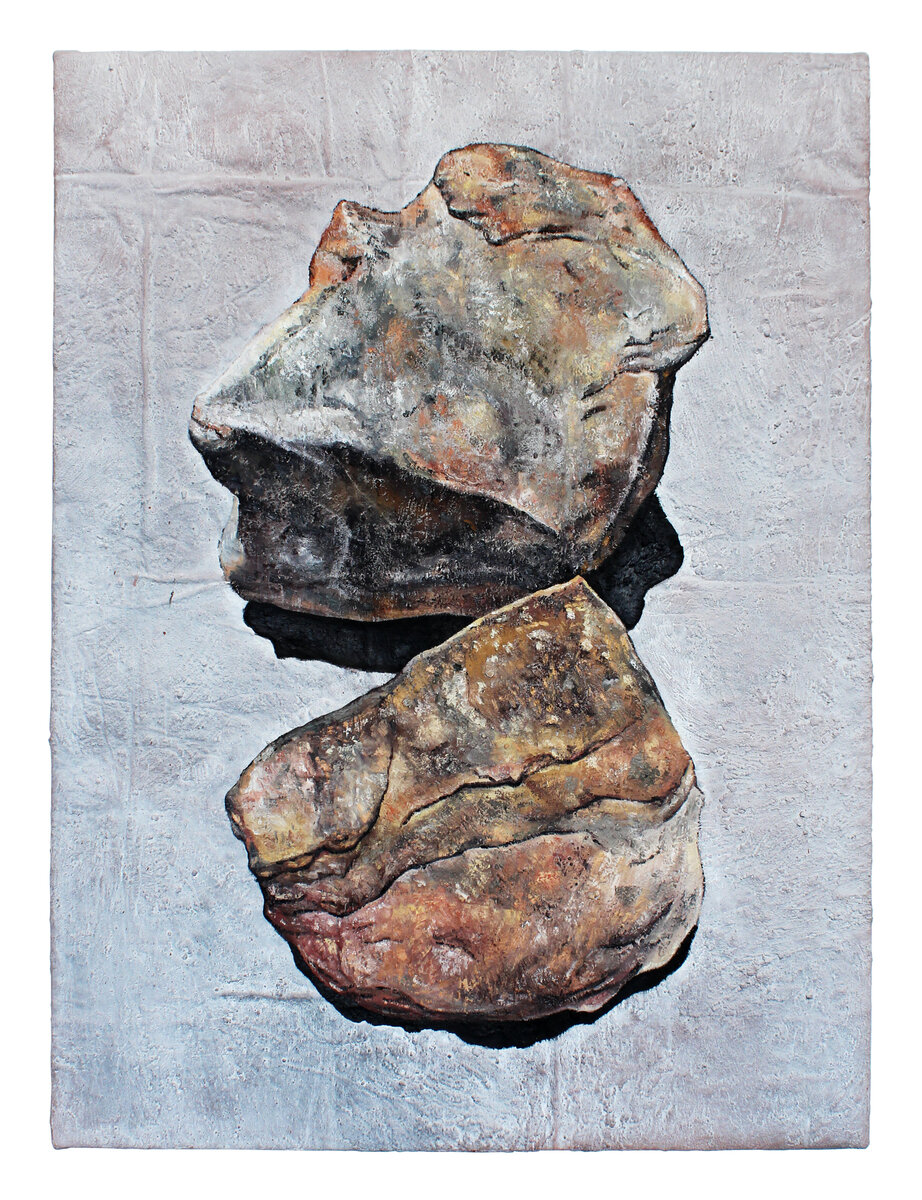

Though it begins with this same topographical process, a painting like Earthworks (Presswood Road II) (2022) initially appears as a realistic painting of rocks. It also includes rocks, real rocks, affixed to heavy canvas. The painted rocks cast painted shadows, giving them that illusionistic appearance of dimension, and presence. At the same time, the rocks in the painting—having the physical dimension that comes from being real rocks protruding from the surface––cast their own, different shadows. Depending on the light, the painted shadow and the cast shadow may diverge. Then there is the issue of the surface, or the ground beneath the rocks: ground here working as a double entendre, as the painting’s ground has been imprinted by and incorporates particles from and an imprint of the ground of Presswood Road, where Johnson first began making this work. (Think Magritte’s The Treachery of Images––i.e., “This is Not a Pipe”––only in Johnson’s painting, this is a rock and also not exactly a rock; these old distinctions, once so profound, have collapsed into each other.)

This approach––the careful engagement with the land, the skilled rendering, the play on light and perception––pulls us away from the conversations about Earthworks as epic, sublime, pure experience, a true engagement with an outside world. Johnson goes out to the landscape, feels its enormity and its degradation, observes its nuances, and then brings back its traces along with its (and our) baggage, conveying something of that whole experience for the rest of us.

Catherine Wagley

But this kind of questing has its own particular history. Because the gallerist and patron Virginia Dwan passed last week, I have been thinking more than usual about this. Dwan, who would go on to fund Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty and Michael Heizer’s Double Negative, started going on scouting missions with Smithson early on––and because she herself had no ambitions to make her own earthworks, to quest itself felt like the point. This desire to be out in the vastness remains relatable, even as given our current self-awareness of manmade damage, the days of making huge gashes or forms perhaps best seen from private planes feel passé. “It is difficult to imagine ourselves existing in the same cultural realm as artists of the past,” Johnson wrote for Psycho Geology, the group show she curated in February. She wondered, also, if art could “paradoxically phenomenalize our lack of agency as a geological force.” The show proposed that there was something afoot, in how Johnson and other artists were grappling with the landscape as we came to understand the urgency of climate change (a phenomenon that is both caused by human action and makes individual humans feel especially small). I recalled this yesterday when, in a theory class I teach, a student wondered if the Anthropocene is itself a new art movement.

When the Nouveaux Réalistes all gathered in Yves Klein’s Paris apartment to form their own movement in 1960, they declared themselves against the art establishment’s intransigence, its refusal to acknowledge the urgency of reality—why for instance were so many ignoring the Algerian War? Whereas the Réalistes meant to embrace “the whole of sociological reality,” to acknowledge it without “any aggression complex, without typical polemic desire.” Their works funnily enough tended still to be paintings––paintings that incorporated found objects, sand, dirt, fire. For them, the problem was the way certain painters painted (i.e., Abstract Expressionists), never the medium. Johnson’s Earthwork are typically paintings (her sculptures are also rectangular like paintings, though much denser). She begins each the same way: in the landscape, adding earth and material (plaster, gesso, water color) to a canvas until it records the typography of the ground. Early on, the Earthworks remained abstract, then they began playing more with “reality” and what that means and looks like in painting.

Though it begins with this same topographical process, a painting like Earthworks (Presswood Road II) (2022) initially appears as a realistic painting of rocks. It also includes rocks, real rocks, affixed to heavy canvas. The painted rocks cast painted shadows, giving them that illusionistic appearance of dimension, and presence. At the same time, the rocks in the painting—having the physical dimension that comes from being real rocks protruding from the surface––cast their own, different shadows. Depending on the light, the painted shadow and the cast shadow may diverge. Then there is the issue of the surface, or the ground beneath the rocks: ground here working as a double entendre, as the painting’s ground has been imprinted by and incorporates particles from and an imprint of the ground of Presswood Road, where Johnson first began making this work. (Think Magritte’s The Treachery of Images––i.e., “This is Not a Pipe”––only in Johnson’s painting, this is a rock and also not exactly a rock; these old distinctions, once so profound, have collapsed into each other.)

This approach––the careful engagement with the land, the skilled rendering, the play on light and perception––pulls us away from the conversations about Earthworks as epic, sublime, pure experience, a true engagement with an outside world. Johnson goes out to the landscape, feels its enormity and its degradation, observes its nuances, and then brings back its traces along with its (and our) baggage, conveying something of that whole experience for the rest of us.

Catherine Wagley